Excerpts from the Secretary of the Navy's 1943-44 annual report to President Franklin D. Roosevelt concluded that for 99 of 100 men wounded during the Normandy landings, the road to recovery began on the beachhead. Expertly trained and equipped Army and Navy medical personnel gave first-aid treatment of life-saving proportions to the initial assault troops during the amphibious attack. Medical care was exacting because of the nature and the severity of the wounds. By the use of plasma, control of hemorrhage and proper splinting, personnel of the U.S. Naval Beach Battalions were able to evacuate those injured whose lives might otherwise have been lost. Urgent life-saving surgery was practiced aboard LSTs and the majority of the 41,035 wounded reaching England for hospitalization were in excellent condition. Penicillin was a crucial component of the medical arsenal in the ETO. The mortality rate of the wounded evacuated from the invasion beaches of France was 3/10 of 1 percent.

Lieutenant Parker's 1943 officer photo, combat helmet, and medical pouch used to treat and evacuate casualties during the Normandy landings. The red arc and battleship grey band painted on his M-1 helmet signifies he is USN in the 5th Engineer Special Brigade. Matching Dr. Parker's uniform sleeve and shoulder marks, the oak leaf and stripes painted on the helmet signifies an officer in the Navy Medical Corps.

Lee Parker, M.D. was a 27-year-old medical officer in the 6th Naval Beach Battalion on D-Day 6 June 1944. His amphibious outfit was formed exclusively for the Normandy invasion, the Allied permanent re-entry into Continental Europe during World War II. The mission of a USN Beach Battalion was to facilitate the landing and movement of troops, equipment and supplies across the invasion beach and the evacuation of casualties and prisoners of war. The Navy Beachmaster, in coordination with his medical officer, provided seaward evacuation of the casualties.

During World War II amphibious warfare, medics and hospital corpsmen were profitable targets and often shot first by the enemy. Unattended casualties piling up on the beach, mutilated and crying out in pain, had a demoralizing impact on the follow-up troops coming ashore. In the Pacific theater, Navy corpsmen took off their crosses and even dyed their bandages jungle green. For the Allied landings in France, OVERLORD planners did not want the Red Cross painted on the helmets of Army and Navy medical personnel of the of the U.S. Engineer Special Brigades. Instead, the distinguishing "white arc" identified Army engineers and the "red arc" was painted on the helmets of beach battalion sailors on Omaha Beach.

U.S. troops march to the ships in preparation for D-Day. Invasion personnel aboard British made LCA and the 6th Naval Beach Battalion aboard LCI(L) 85, 88, and 89 at Weymouth, a seaside town in Dorset, England on the Channel coast. The New Yorker war correspondent A.J. Liebling was aboard LCI 88 and promised "a front row seat" for the Normandy invasion.

Just one year before the cross-Channel attack, nine young Navy medical officers were ordered to "proceed without delay to Norfolk, Va., and report to the Commanding Officer, Amphibious Training Base, Camp Bradford, Naval Operating Base, for duty with Beach Battalion No. 6, and for duty outside the continental limits of the United States."

Frank M. Ramsey, Jr., M.D. (A-1)

John E. Daughtrey, M.D. (A-2)

Lee Parker, M.D. (A-3)

Ralph A. Hall, M.D. (B-4)

Eugene D. Guyton, M.D. (B-5)

James F. Collier, M.D. (B-6)

Michael M. Etzl, M.D. (C-7)

J. Russell Davey, Jr., M.D. (C-8)

John F. Kincaid, M.D. (C-9)

The U.S. Naval Beach Battalions were a product of World War II. After Dunkirk, Crete, and Corregidor, when the Allied command realized that territory lost to the enemy could be regained only by invading the coast of Europe, amphibious warfare evolved dramatically. OVERLORD planners could put assault troops ashore with the aid of huge fleets of ships and an umbrella of air support. The massive assault force could fight its way inland but to stay there, it had to be supplied with food, weapons, ammunition, artillery, tanks and medical support. Moving men and equipment across the invasion beaches and providing seaward evacuation of the casualties became the D-Day mission for the amphibious sailors of the 2nd, 6th and 7th Naval Beach Battalions in Normandy. Supporting the assault from the sea, these naval forces were essential components of the U.S. Army's Engineer Special Brigades, responsible for organizing the American landings in France.

Southern England was becoming one vast military camp in May 1944, crowded with soldiers and sailors, surrounded by barbed-wire entanglements and 2,000 Counter Intelligence troops. Assault personnel were prevented from leaving camp with secret information of the impending attack. The 6th Naval Beach Battalion spent several weeks in the marshaling area near the town of Dorchester. During the period of confinement, no passes were issued and mail was forbidden. From May 26th through June 2nd, Army and beach battalion personnel were taken into camouflaged circus-size tents and shown maps, photo-strips and sand table models of the assault beaches. The fifty-foot-long tables included plaster of Paris models and aerial photographs of the beach indicating the exact location of machine gun emplacements, pillboxes and beach obstacles. The battalion was assured that as a result of a massive air and naval bombardment of the Normandy coast, "every grain of sand will be turned over twice before the first wave hits the beach." Intelligence officers emphasized that the Germans who manned the area behind Omaha Beach were second rate, older troops and there would be little resistance. "Don't be afraid or ashamed of being afraid - just do your job!"

U.S. Coast Guard photo of LCI invasion flotilla with barrage balloons and "Morning of D-Day from LST" watercolor by Mitchell Jamieson. A barrage balloon is tethered with metal cables, used to defend against low-level aircraft attacks by damaging the plane on collision with the cables and attached explosives. The LCIs, according to war correspondent Ernest Hemingway, "were the only amphibious operations craft that look as though they were made to go to sea. They very nearly have the lines of a ship."

Fifty war correspondents received permission from General Eisenhower to accompany the assault troops and witness D-Day. Dispersed among 150,000 troops headed for the Normandy beaches, invasion journalists were promised "a front row seat" for what some predicted would be the most significant day of modern times. In the 5,000-ship invasion armada, during the 100-mile-Channel-crossing, Dr. Parker, from Waycross, Georgia, was aboard the USS Dorothea Dix with war correspondent Ernest Hemingway. Twelve miles from the Normandy coast, Parker and Hemingway were scheduled ashore in one of the twenty-three 35-foot LCVPs carried by their troop transport. "The mine sweepers were ahead of us and the smaller boats that were slower, the LCIs, were ahead of us," said Dr. Parker. "When I got up on top of the Dorothea Dix, up on the flying bridge, and I managed to get up there, as far as you could see, to the front of you, to the back of you, to the right, to the left, you didn't see anything but ships. And then when you looked overhead, there was nothing but planes with black and white stripes on them."

Invasion planners had promised a protective bomb crater for every man going ashore on D-Day. Daylight landings were essential so that the navy and air force could bombard the beach accurately. Due to the cloud cover over the Omaha Beach assault area, General Eisenhower and the Eighth Air Force ordered a deliberate delay of several seconds in its release of bombs in order to insure that they were not dropped on assault landing craft in the Channel. Unfortunately, 13,000 bombs dropped by 329 B-24 bombers did not hit the enemy coast defenses at all but were dispersed as far as three miles inland.

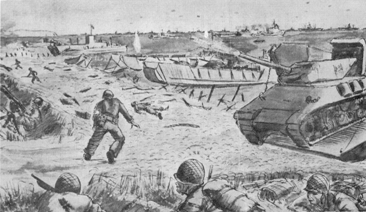

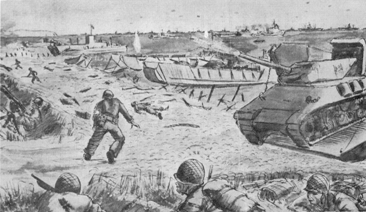

"The Battle for Fox Green Beach" by U.S. Navy Combat Artist Dwight Shepler, 1944

The 6th Naval Beach Battalion went ashore early in the morning of D-Day, just after the gap assault teams (Navy Combat Demolition Units and Army engineers) and troops of 1st Infantry Division sustained heavy casualties. Responsible for the area between the low tide mark and the high tide mark, the mission of Dr. Parker's 400-man beach battalion was to organize the eastern half of Omaha Beach in the invasion sectors code-named Easy Red, Fox Green and Fox Red. The Beachmaster, whose duties have often been described as similar to "a traffic cop at a busy intersection in hell," controlled all boat traffic coming onto the beach and then through his medical doctor, arranged for the shore-to-ship evacuation of the casualties.

At 0735 on D-Day, Commander Carusi, Beachmaster Vaghi, Dr. Davey, and C-8 platoon went ashore an apparent military disaster. Bodies of the dead and dying littered the sand as far as the eye could see; the gap assault teams were so badly decimated that only a few lanes were blown through beach obstacles and mines. With many of the casualties medically beyond help, Dr. Davey ordered his corpsmen to treat only injured personnel who could be saved. An hour later, the battalion was nearly decapitated when Beachmasters Jack Hagerty, G.E. Wade, Len Lewis, and Jimmy Allison were killed; three officers and two hospital corpsmen died before reaching the beach.

Despite near-catastrophic conditions on Omaha Beach, Dr. Parker and his A-3 corpsmen struggled ashore Easy Red and headed for the Fox Red sector. "Movement on the beach was made extremely hazardous by heavy fire and by the large number of mines which had become detached from the obstacles and became buried in the sand. In addition to these hazards," wrote COL W.D. Bridges of the Engineer Special Brigades, "there were many burning vehicles along the beach sending showers of projectiles from exploding ammunition and fragments of metal as mines and demolition materials exploded."

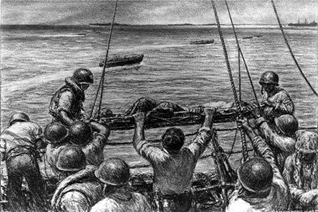

LCVP "Assault Wave Cox'n" watercolor by Combat Artist Dwight C. Shepler. Personnel of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade make a rescue on the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach.

The preparatory air and naval bombardment was ineffective, leaving many German guns in position to fire on the attackers. ''The casualties were absolutely appalling,'' said Dr. Parker. Artillery from the ships in the Channel was supposed to have created craters for soldiers to take cover in, but the big shells fell short. ''We were told we would have so many foxholes and bomb craters we could jump into” Parker recalled. “I didn't see a one.'' And most of the tanks that were supposed to help blast through the German fortifications had sunk, launched too far out in heavy seas, contributing to the high casualty rate on Omaha Beach.

Officers of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade "found that the gap assault teams, severely decimated by the fierce enemy fire, were far behind schedule in clearing gaps in the beach obstacles." Officers and men of Dr. Parker's battalion "worked side by side with these teams in clearing the obstacles under the heavy fire on the beach. The gaps were frequently interdicted by enemy artillery fire, which caused numerous casualties."

Two platoons of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion worked their way up to the shingle bank with three surviving DD tanks which were seen to knock out several enemy pillboxes, while another 6th Beach Battalion detachment attempting to get ashore had to abandon its LCVP 100 yards from Easy Red when it struck an obstacle and was badly damaged by machine gun fire. Other battalion elements set up control stations on the beach to direct the landing of craft and salvaged equipment to mark safe lanes of approach. A detail from Company C helped rescue two platoons of infantrymen from the water. These men had debarked in deep water and their load of equipment was pulling many men down. "We lost many men to bullets but also we had many drown. The drowning of our soldiers was not publicized that much but we lost many to the icy water," said Dr. Parker. "Many of the wounded soldiers were in shock and it wasn't always easy to tell the living from the dead among the hundreds of bodies that lay on the beach or washed in the surf."

Beyond the beachhead in the hedgerows, the killing and wounding of aidmen by German rifle fire was carefully studied. By July, medical commanders concluded that a high proportion of casualties were shot from the unbrassarded right side; Germans by and large were following the Geneva rules of land warfare. Accordingly, U.S. aidmen began wearing brassards on both arms and painted nonregulation red crosses on their helmets. (Fighting For Life by Albert E. Cowdrey)

During the initial D-Day attack, German snipers would pick off exposed medics and hospital corpsmen while they treated the wounded on the beach. The medical teams, forced to drag casualties from the surf toward the enemy's murderous guns, became casualties themselves. Under punishing fire, battalion aidmen worked up and down the beach and in the minefields, bandaging, splinting, giving morphine, and plasma. Army and Navy doctors, often themselves injured, worked as they could to give emergency treatment. The Geneva Convention Red Cross brassard made the aidman's job one of the most hazardous on the beach.

While working next to Dr. Parker on the Fox Red sector of Omaha Beach, Dr. Frank Ramsey was seriously injured when a chunk of his shoulder was blown off by a Nazi artillery shell. Refusing evacuation, he suffered intensely on a stretcher while providing triage instructions for his USN corpsmen.

The dead who carried supplies ashore in the early morning of D-Day made it possible for the seriously injured to survive later in the day. Severe enemy opposition resulted in the loss of a large part of the medical supplies brought ashore by Army and Navy personnel. A surgeon of the 16th Regimental Combat Team noticed a high proportion of casualties caused by rifle bullet wounds in the head. Wounded men, lying on the exposed sand, were frequently hit a second or a third time. Medics searched the casualties and from them they took special first aid kits containing pain-alleviating morphine, sulfas and bandages. They salvaged blankets and medical supplies which floated up with the tide.

OMAHA BEACH "Infantry men were pinned down on the beach by enemy fire from the hill behind the beach. LCTs bring in tanks and LCIs unload more infantry. A destroyer moves in to give close fire support while a cruiser delivers supporting fire in the background. A beach battalion Naval Hospital Corpsman goes to the aid of the wounded soldiers." AMPHIBIOUS OPERATIONS, INVASION OF NORTHERN FRANCE, WESTERN TASK FORCE, JUNE 1944.

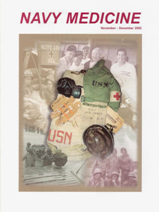

Army and Navy aidmen were universally praised by D-Day veterans as the bravest of the brave. In Dr. Parker's A-3 platoon, 19-year-old Jerome Alberts described the D-Day conditions on the Fox Red sector of Omaha Beach. "Thousands of mangled bodies were strewn about, and hundreds of others were in agony awaiting evacuation. The task lay before us. Signal the Ships in! Stretcher bearers! Corpsmen! There was not an idle man. By noon, landing craft and Rhino ferries were taking them to hospital ships. I take my hat off to the medics, both Army and Navy. The work of Dr. Lee Parker, of our platoon, stands out in my mind. That man was everywhere and every place. One minute he was ten feet from me giving a man plasma, five minutes later he was aboard a beached LCT, treating scores of other wounded." (Navy Medicine November - December 2000)

Retreat was not an option on 6 June 1944. OVERLORD commanders considered abandoning U.S. troops on "bloody" Omaha and redirecting the entire American assault through Utah Beach. Against all odds, Dr. Parker's 6th Naval Beach Battalion, attached to the 5th Engineer Special Brigade, managed to organize the invasion landings and provide casualty evacuation on the eastern sector of Omaha Beach. "The medical sections performed their duties in an especially heroic manner" wrote Colonel W.D. Bridges, Corps of Engineers. "They collected casualties, gave first aid and evacuated the casualties to landing craft. Groups of casualties on the beach were subjected to heavy concentrations of mortar fire, and craft were under observed artillery fire the entire time they were grounded."

Officers of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade wrote in their unit history, "The operations of the naval beach battalions attached to the brigades can be said to represent the ideal in Army-Navy cooperation. Battalion commanders maintained constant liaison with their brigade commanders, and, prior to the operation, companies participated in many exercises with the engineer combat battalions which they supported. In this way a high degree of mutual respect was developed between Army and Navy personnel, and a division of responsibilities was clarified during the training period."

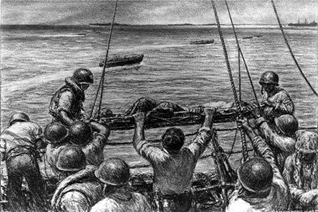

Life-saving medical care on "Easy Red" Omaha Beach and "The Way Back" for the 100-mile-Channel-crossing to the UK by Lawrence Beall Smith. "The extraordinary gallantry, heroism, and determination displayed in overcoming unusual difficulties and hazardous conditions and the esprit de corps displayed by the 6th Naval Beach Battalion contributed materially to the capture of Omaha Beach and reflect highest credit on personnel of this organization and the Armed Forces of the United States." (COL W.D. Bridges)

"During the operation itself, it was noted that no plane of cleavage existed between naval beach party and Army elements. The naval beach battalions in some instances furnished dozers for road construction and personnel to direct traffic off the beaches. On the other hand, Army personnel helped to clear underwater obstacles. Perhaps the best example of complete cooperation was found among the medical personnel of the beach battalions and the brigades. Here the feeling was especially marked that a job had to be done and that the definition of responsibilities should not stand in the way of accomplishing a mission." (Operation Report Neptune 1944)

The principal task of the Navy Medical Department was that of shore-to-shore evacuation. The amphibious beach battalions in France represented the "far-shore link" in the medical evacuation chain. The "far-shore" phase included medical aid, exchange of supplies and shore-to-ship evacuation of the casualties. Although there were many unavoidable delays, especially during the early hours of D-Day, the securing of craft for seaward evacuation was the responsibility of the beach battalion medical officer through the Navy Beachmaster. Once aboard the hospital LSTs, surgery and expert medical treatment was administered during the 100-mile-Channel-crossing, the "middle link" in the Navy evacuation chain. The Army "near-shore" casualty reception link in Great Britain was augmented by 35,000 beds and hospital equipment shipped from the U.S.A., the equivalent of shipping about 12 complete New York City Bellevue Hospitals, except the buildings. Of all the U.S. servicemen wounded on the "bloody" beaches of France, more than 99% evacuated back to England by the U.S. Navy survived the invasion.

General Omar Bradley's First U.S. Army Report of Operations concluded, "Combined training with the Navy Medical Department is a must. Too much cannot be said about the part which the navy played in the early days of the landing operation."

The 6th Naval Beach Battalion was commissioned 9 October 1943 under the command of 39-year-old Eugene C. Carusi, USNR, an Annapolis graduate and Washington D.C. attorney. The battalion was attached to the 5th Engineer Special Brigade 12 April 1944. Commander Carusi got an anti-aircraft shell in the chest on the night of D+3 and was evacuated the following day. According to The New Yorker war correspondent A.J. Liebling, "Carusi says that he was lying outside the dugout awaiting evacuation next morning, when one medical corpsman said to another, 'No use taking that white-haired old sonofabitch. He won't make it.' It made Gene so sore he ordered them to take him. They got him back to England and he survived."

Carusi's executive officers were Lieutenants Ed Reardon and Henry Watts, both New Yorkers. Watts took over the battalion after Causi was hit. After the war, Henry Watts became chairman of the Board of Governors of the New York Stock Exchange.

Lord Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations, designed the Allied Combined Operation shoulder patch above – gold tommy gun, anchor and eagle on a blue field, signifying combined operations on land, sea and air. The blue patch was worn by the U.S. Army Engineer Special Brigades. The round patch was worn by the British Commonwealth Commandos and the red and gold patch was later authorized for the U.S. Naval Beach Battalions. Lord Mountbatten personally showed the patch to President Roosevelt.

COL W.D. Bridges, one of the top Army commanders of D-Day proposed a Unit Citation for the 6th Naval Beach Battalion. Bridges wrote a letter to Commander Carusi in which he proudly announced that Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk, responsible for the cross-Channel transport of all U.S. forces in Normandy, had approved the Army's recommendation for a Unit Citation. Bridges, head of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade, proposed that the 6th Naval Beach Battalion be cited for "extraordinary heroism and outstanding performance of duty in action while supporting the assault landings on the Vierville-Colleville sector, Omaha Beach, Normandy, France, 6 June 1944." Bridges wrote, "It gives me a great deal of personal satisfaction to advise you that this recommendation and proposed citation has been forwarded by Admiral Kirk, Commander of U.S. Forces, France, to the Secretary of the Navy recommending approval. A copy of the endorsement is enclosed herewith for your information…To you personally and to the men of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion, I attribute a very tangible share of the successful establishment of the Omaha Beachhead. But for this aid the precarious situation on the Beach might have been turned to disaster…My very, very best to you, your officers and all your men."

6th Naval Beach Battalion Casualties

Killed in action: 4 Officers, 18 Enlisted Men

Wounded in action: 12 Officers, 55 Enlisted Men

The endorsement that Admiral Kirk sent to the Secretary of the Navy on 26 February 1945, recommended that the citation be approved immediately. "The actions of the SIXTH Naval Beach Battalion as a unit contributed immeasurably to the future success and security of the Allied Nations, the United States Army and United States Navy, and were performed in accordance with the highest traditions of the United States Navy."

The Unit Citation recommendation and Kirk's endorsement was never acted upon by the Navy Department and for the next five decades, authors of D-Day rarely mentioned the beach battalions in Normandy. Then, along came Jonathan Gawne and Jan Herman.

Dr. Parker and Medical Historian Jan Herman, BuMed, in France on the May-June 1999 cover of Navy Medicine magazine and "Hauling the Sling Gently Over the Rail" by Kerr Eby

In 1995, I made an inquiry to learn more about my father, who died in 1948; Dr. Davey was Beachmaster Joe Vaghi's medical officer on D-Day. The Naval Historical Center wrote, "Our records dealing with Naval Beach Battalion operations are sketchy and we do not hold reports for the 6th Naval Beach Battalion." However, they did send an article appropriately titled, The U.S. Naval Beach Battalions: The Forgotten Sailors of The Invasion Beaches (1991) by Jon Gawne.

In the most definitive Normandy invasion book published, Spearheading D-Day: American Special Units in Normandy (1998), Gawne wrote, "Of all the special units that took part in the Normandy operation, none have been so forgotten as the Navy Beach Battalions. These sailors, serving under Army command, played a vital role on the beaches not only on D-Day, but for the weeks that followed. The Navy, for the most part, has all but forgotten them."

Fifty-seven years after D-Day, veterans of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion "spearheaded" a Department of Defense documentary - Navy Medicine at Normandy D-Day June 6, 1944 - produced by the Naval School of Health Sciences in cooperation with the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. Dr. Lee Parker and Navy medical historian Jan Herman returned to Normandy, France for on-location filming and identification of USN "far-shore" evacuation sites. In the masterful re-creation of the cross-Channel assault, Director Jack Lewin combines on-screen interviews of D-Day veterans with 1944 invasion film. The Surgeon General of the Navy, VADM Richard A. Nelson and the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States (AMSUS) invited military guests, veterans and their families for the 21 May 2001 premiere of the documentary at the U.S. Navy Memorial in Washington, DC.

Left to right, Historian Jan Herman, Corpsman Vince Kordack, Beachmaster Joseph Vaghi, Dr. Richard Borden, Dr. Joseph Brennan, Dr. Lee Parker and Director Jack Lewin at the U.S. Navy Memorial premiere of Navy Medicine at Normandy D-Day June 6, 1944. After World War II, having "received their calling" on bloody Omaha Beach, both Joe Brennan and Dick Borden entered medical school.

Navy Medicine at Normandy

http://www.navytv.org/channel.cfm?c=139

Chapter 1, 2, 3 & 4

On Navy TV

The United States Navy Memorial

Dr. Parker told a reporter in June 1994, "Late in the afternoon on June 6, 1944, I saw American bodies floating in the water as I worked on wounded soldiers until the sun went down. I never forgot this day or the next 21 days I stayed on Omaha Beach. When I returned to the scene in 1987, I was the only person on the beach and as I walked the beach, many memories came back."

Lee Parker, now 94, does not consider himself a war hero. "The men who didn't come home are the real American heroes." Less than six months after D-Day, he received word that his brother, Lieutenant Jack Parker, had been killed in action. "It's bad to see a 17-year-old come up with the loss of a leg, the loss of an arm, certainly the loss of life. War is hell. It's not to be glorified in any way."

More than half a century after the United States and British Commonwealth forces landed on the beaches of Normandy on 6 June 1944, the following message was received from U.S. Senator Jesse Helms, Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee:

"On the occasion of the 56th reunion of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion, it is a great pleasure to announce that on June 14, 2000 the Army Unit Awards Board approved the awarding of the Presidential Unit Citation for the Battalion.

More than half a century has elapsed since the Allied victory extinguished the dark flame of fascism before it could consume the entire earth. It is easy to forget the terrible sacrifices and the tragic losses that were necessary in order to achieve the ultimate victory of good over evil, of freedom over subjugation. But it is at the peril of ourselves and our children that we do so.

For though I firmly believe that God was on our side, I also believe that the Allied victory was not preordained but instead was a result of planning, preparation, and - above all - the heroism displayed by folks like those in the 6th Naval Beach Battalion. The distinguished honor of a Presidential Unit Citation is well deserved - and long overdue!

Likewise, our country owes a debt of gratitude to the families of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion who endured many hardships while their loved ones were away.

This Senator will always be grateful to the brave Americans who unhesitatingly put their lives on the line during the Second World War and ensured the survival of our republic.

God bless you - and God bless America."

Dr. Lee Parker, Only Living Navy Surgeon From D-Day Invasion On Omaha Beach, Earns French "Legion Of Honor Medal" ~ During the French Legion of Honor Ceremony, held on Wednesday, September 7, 2011, Greensboro native, Dr. Lee Parker, was awarded the prestigious Legion of Honor Medal. Dr. Parker, a retired physician and World War II veteran, joined sixteen other veterans that were being recognized for their valor and service during the war. The Legion of Honor was created by Napoleon in 1802 to acknowledge services rendered to France by persons of great merit. Dr. Parker received a letter from the French Ambassador, Francois DeLattre, in which he informed the retired physician that "by decree of President Sarkozy on July 4, 2011, you have been appointed a 'Chevalier' of the Legion of Honor. This award testifies to President Sarkozy's high esteem for your merits and accomplishments. In particular, it is a sign of France's infinite gratitude and appreciation for your personal and precious contribution to the United States' decisive role in the liberation of our country during World War II." The Herald-Journal, Greensboro, GA

The Lone Sailor

The U.S. Navy Memorial Foundation: www.lonesailor.org

Reprint from the Fall 2001 issue

"Normandy Allies"

Nearly 60 years after the fact, high school students are learning about the Sailors of the largest armada in history.

On July 10, the Navy Memorial Foundation's Education Institute explained the Navy's role in the 1944 D-Day invasion to student participants of the Normandy Allies international Experience 2001.

"Your presentation assisted us greatly in attempting to visualize an event which is now so hard to imagine when standing on those shores," said Normandy Allies, Inc. President Marsha Smith.

Few histories of the 1944 Allied assault on Normandy discuss the role of the sea services in-depth. The Education Institute's presentation explained the roles of the many ships involved in the attack, from battleships to transports to assault craft. Contributions of the Sailors on the beach, the beachmasters, signalmen, and medical personnel of the 6th and 7th Navy Beach Battalions, also received special attention in the presentation.

The program's 12 student participants, selected from across the U.S., visit sites in Washington, the D-Day Museum in New Orleans, pre-invasion sites in England, and the beaches of France. Normandy Allies, Inc., a non-profit organization, conducts the program, which is now in its third year.

By seeing slide presentations, photographs, and artifacts - including an original set of coxswain's invasion maps - students learned of the invasion force's naval organization, the specific missions of individual ships and units, and the impact of the tens of thousands of Sailors who participated at Normandy.

"The lesson carried over very well as we stood on Omaha and Utah beaches," Smith said.

Students also saw a new Navy video production, "Navy Medicine at Normandy: June 6, 1944." The video presents interviews of doctors, hospital corpsmen, and other Sailors and Coast Guardsmen who assisted casualties on the French beaches.

"The medical aspect is often overlooked," said Smith. "I feel the significance of studying this - or at least opening the door to students' understanding of the medical components - is vital to our program and our mission."

www.normandyallies.org

THE SILVER STAR MEDAL

POSTHUMOUSLY AWARDED SECOND LIEUTENANT JACK S. PARKER, INFANTREY, 5TH ARMY, 88TH DIVISION, 1944.

THE AWARD IS MADE TO MRS. ANNA C. PARKER, WIDOW

CITATION

FOR GALLANTRY IN ACTION ON 6 OCTOBER 1944 NEAR HILL 99. SECOND LIEUTENANT PARKER DISPLAYED EXCEPTIONAL GALLANTRY IN ENEMY FIRE AT THE COST OF HIS LIFE WHILE ASSAULTING GERMAN POSITIONS. APPROACHING THE OBJECTIVE THROUGH HEAVY ENEMY MACHINE GUN AND AUTOMATIC RIFLE FIRE FROM A HOUSE ON A HILL, SECOND LIEUTENANT PARKER LED HIS PLATOON TO WITHIN SEVENTY-FIVE YARDS OF THE CREST. ENEMY MACHINE GUNS ON THE FLANKS SUDDENLY POURED MURDEROUS CROSSFIRE INTO THE MEN, CAUSING NUMEROUS CASUATIES. CHARGING UP THE SLOPE IN THE FACE OF CONVERGING STREAMS OF HOSTILE FIRE, MACHINE PISTOLS SPRAYED LEAD INTO THE ATTACKERS, CUTTING DOWN MEN FOLLOWING THIS INTREPID OFFICER. RUSHING TOWARD THE BUILDING WITH NO REGARD FOR THE GRENADES HURLED AT HIM, SECOND LIEUTENANT PARKER SAW GERMANS AT THE REAR OF THE HOUSE. HIS WEAPON BLAZING AS HE ADVANCED HEEDLESS OF THE INTENSE FIRE, SECOND LIEUTENANT PARKER CUT DOWN THE GERMANS, KILLED NINE OF THEM AND LED HIS MEN INTO THE CENTER OF THE ENEMY DEFENSES. CONSTANTLY EXPOSED TO THE FULL FURY OF HOSTILE FIRE AS HE DIRECTED THE MOVEMENTS OF HIS TROOPS, SECOND LIEUTENANT PARKER CONTINUED TO LEAD THE WAY FORWARD, FIGHTING HIS WAY OVER A SMALL RIDGE, POURING BULLETS INTO THE SUPPORTING ENEMY POSITIONS. ASSULTING IN CLOSE RANGE OF THE EMPLACEMENTS, HE WAS KILLED IN THE FIRE TO WHICH HE WAS EXPOSED. SECOND LIEUTENANT PARKER'S AGGRESSIVE LEADERSHIP AND GALLANT ACTION AT THE COST OF HIS LIFE ENABLED THE QUICK SEIZURE OF THE OBJECTIVE AND WAS AN INSPIRATION TO ALL WHO KNEW OF HIS DEED. HIS GALLANTRY IN THE PAGE OF HOSTILE FIRE REFLECTS THE FIGHTING TRADITION OF THE INFANTRY LEADER.

BuMed Interview with Lee Parker, M.D. under construction

Back to Top

Back to Top