US Navy commander Erik R. Nilsson, left, Beachmaster Unit ONE commanding officer, salutes Frank Walden after pinning the Bronze Star onto his jacket at a ceremony in Coronado Wednesday afternoon. Photo by John Gastaldo

By Nathan Max

U~T San Diego News

June 6, 2012

Reprinted with permission

CORONADO — Frank H. Walden was among the first wave of military personnel to storm the beaches of Normandy, France, on D-Day almost seven decades ago.

On the 68th anniversary of one of the most memorable days of his life, Walden became the first of his battalion to receive the Bronze Star, after the Navy recognized his medical unit’s exemplary record during World War II. The rest will soon follow.

Walden, 86, received the award Wednesday afternoon during a change-of-command ceremony for Beachmaster Unit One at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado. Afterward the octogenarian from Northern California, who also received the U.S. Army’s Combat Medical Badge, described it as "awesome."

"It makes me feel that I was worth it," Walden said, as he gazed over the special case containing the U.S. Armed Forces’ fourth-highest combat award.

"They gave us a job to do, and we did it. (Awards) were the last thing we thought about. I got out of there with my life. I figured that was enough."

Walden, who was born in Oakland and now lives in Walnut Creek, was injured that day, suffering shrapnel wounds and a broken shoulder. None of those injuries had lingering effects, however, and he eventually came home to have a successful career as a firefighter.

Walden’s story is like many others who lived out history on Omaha Beach, but it is no less remarkable.

In late 1942, at age 17, Walden enlisted in the Navy because he "felt the need," and at the time, "that’s what everybody did."

By the time D-Day approached, he was a hospital apprentice first class and was pegged for the initial wave of the invasion. During the tumultuous trip over the English Channel, machine gun fire whizzed over Walden’s head, the boat hit a sandbar, the radio man lost his gear and one of the ramps blew up. Everyone on his boat had to disembark off one ramp.

Once Walden hit the beach at around 8:30 a.m., he said he immediately started treating the wounded, administering triage and morphine, and pulling lifeless bodies out of the water. Walden said he could not remember how many soldiers he treated, but he estimated it to be dozens upon dozens.

After tending to his comrades for about 10 hours, Walden was himself wounded. Walden said he and a 16-year-old fellow corpsman, Virgil Mounts, saw a shell explode near two Army personnel who were carrying a stretcher. When Walden and his friend went to treat them, another shell blew up, killing Mounts instantly.

The blast injured Walden, who managed to walk to the next beach over, and he was quickly transported back to England. Walden never returned to the European theater of operations.

"It was horrible," Walden, also a French Legion of Honor recipient, said of his one day in Normandy. "I’ll never forget it. You try to, but the memory is always there."

Walden is one of 84 members of the 6th Naval Beach Batallion who will receive the Bronze Star for their bravery during World War II. For those who have died, their family members will get the award on their behalf.

The 6th Naval Beach Battalion corpsmen provided triage and casualty evacuation for Army assault troops of the 1st Infantry Division at the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach. The 6th Naval Beach Battalion is the precursor to today’s Beachmaster Units.

The Secretary of the Navy approved the awards just two weeks ago, said Navy spokesman Richard Chernitzer.

US Navy commander Erik R. Nilsson, left, Beachmaster Unit ONE commanding officer, shakes the hand of Frank H. Walden, a Hospital Apprentice 1st Class who received his Bronze Star for service on Omaha Beach, D-Day, June 6, 1944. Walden and his wife Barbara Walden, right, are from Walnut Creek. Photo by John Gastaldo

Earlier this year, the son of the man who led the initial medical attachment ashore approached Capt. Ed Harrington to inquire about the unit’s eligibility to receive the U.S. Army Combat Medical Badge. Harrington, the commodore of Naval Beach Group One, ran the inquiry up the chain of command, and in March the U.S. Army awards board approved the Combat Medical Badge and also awarded the 84 men with the Bronze Star.

It became official when the Navy followed suit two weeks ago, Chernitzer said.

The unit spent three weeks on the beach, and during that time the mortality rate of the 41,035 wounded men who were evacuated back to England was just 0.3 percent.

Walden was the first to receive his Bronze Star. Others will be honored at an East Coast ceremony later this year.

"To me, it was special to be a part of recognizing this guy," said Lt. Cmdr. Gregory Milicic, operations officer for Beachmaster Unit One. “"It gives me more perspective of what we’re doing today. Frank Walden and his shipmates in the 6th Naval Battalion, and everyone who served on D-Day, they’re pretty incredible to me."

*****

Medical doctors are rarely sent ashore in the "spearhead" of an amphibious attack. The mission of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion aidmen on Normandy D-Day was to provide triage and medical treatment for initial assault troops of the 1st Infantry Division, and through their Navy Beachmaster, arrange for casualty evacuation. "The medical sections performed their duties in an especially heroic manner" wrote D-Day commander Colonel W.D. Bridges, Army Corps of Engineers. "They collected casualties, gave first aid and evacuated the casualties to landing craft. Groups of casualties on the beach were subjected to heavy concentrations of mortar fire, and craft were under observed artillery fire the entire time they were grounded."

Recently, an inquiry was made to determine if medical officers and corpsmen of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion were eligible for the Combat Medical Badge (CMB). My father, Lieutenant J. Russell Davey, Jr., MC, USNR, was a member of this amphibious outfit, but unfortunately died after the war in 1948. However, 96-year-old Frank Ramsey, M.D., 95-year-old Lee Parker, M.D., 87-year-old Richard Borden, M.D., and a handful of USN corpsmen, including 93-year-old Paul Aeisi, were living at the time of the inquiry. Drs. Parker and Borden both lost their brothers during World War II. Drs. Joseph R. Brennan and Richard Borden were teenage corpsmen on D-Day and after the war, entered medical school.

Navy corpsman "Ready for Duty" oil on canvas, 1943, by Irwin Hoffman, Gift of Abbott Laboratories. On the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach, "The Tough Beach" watercolor by Navy Combat Artist Dwight Shepler, on D-Day 6 June 1944. In the foreground is USS LCI(L) 93, aground, holed, and lost. This USCG vessel received at least "ten direct hits, two passing through the pilot house, two through the starboard bow at the forecastle and the remainder along the port side." Courtesy U.S. Navy Art Collection, Washington, D.C.

One year before the 1944 cross-Channel attack, nine young doctors just out of medical school were ordered to "proceed without delay to Norfolk, Virginia, and report to the Commanding Officer, Amphibious Training Base, Camp Bradford, Naval Operating Base, for duty with Beach Battalion No. 6, and for duty outside the continental limits of the United States."

Frank M. Ramsey, Jr., M.D. (A-1)

John E. Daughtrey, M.D. (A-2)

Lee Parker, M.D. (A-3)

Ralph A. Hall, M.D. (B-4)

Eugene D. Guyton, M.D. (B-5)

James F. Collier, M.D. (B-6)

Michael M. Etzl, M.D. (C-7)

J. Russell Davey, Jr., M.D. (C-8)

John F. Kincaid, M.D. (C-9)

After intensive amphibious training in nine designated platoons at Camp Bradford, Little Creek, Virginia, near the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay, and Fort Pierce, Florida, the 6th Naval Beach Battalion was commissioned 9 October 1943 under the command of Eugene C. Carusi, USNR, an Annapolis graduate and Washington D.C. attorney.

After another two months of amphibious training back at Camp Bradford, the battalion was transported by train to Lido Beach, Long Island, which served as a staging area for deployment overseas. On 6 January 1944, the battalion was bussed to New York City’s Hudson River terminal of the Cunard White Star Line at Chelsea Piers, a major embarkation point for troop carriers that took American servicemen to the European theater during World War II. Falling in single file, the battalion was led up a freight ramp into the lower deck interior of the RMS Mauritania II, a converted troopship.

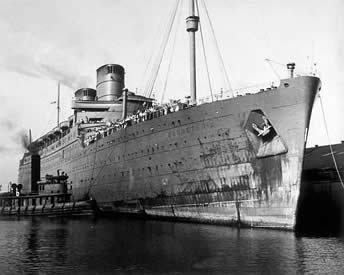

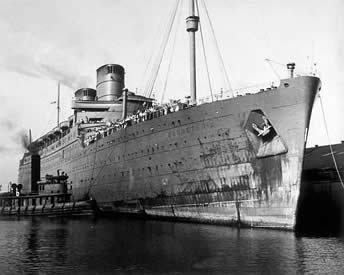

The RMS Mauritania troopship docked at New York’s Chelsea Piers, not far from today’s INTREPID Sea, Air & Space Museum. The color photo was taken next to the INTREPID, while aboard the amphibious USS New York LPD-21 transport, forged from the steel of the World Trade Center.

On 7 January 1944, the 6th Naval Beach Battalion sailed from the port of New York City down the Hudson River aboard the RMS Mauritania. In an 8 January 1944 V-MAIL to his wife, 26-year-old Dr. Davey wrote, "Well, as usual everything happens to the 6th Beach Battalion. We had at last apparently got under way and were just about heading for open sea when, during our first Abandon Ship drill, we ran into an oil tanker. Not much damage was done to either ship but because the Pilot was still in command of our ship, he had to put back to port to report the incident. So here we are, back in New York harbor, tied up to the same dock which we had left but a few hours before. I believe that the damage has been repaired by now and we hope of shoving off soon again. It was certainly a strange and almost unbelievable sight to see two large ships approaching each other at right angles, both ships refusing to give way to the other. We all could see that they must collide but couldn’t believe such a thing possible. However, it did happen and I’m glad to say that our ship, being the larger, rolled a lot less than did the tanker."

The 6th Naval Beach Battalion sailed again from the port of New York and traveled overseas on the Mauritania to the UK in preparation for the invasion of Normandy. The ship docked in Liverpool 17 January 1944 and the beach battalion was transported to Salcombe, Wales for advanced amphibious warfare training.

In the ETO during World War II, the greatest neutralizing threat on Normandy D-Day was the Nazi use of poison gas; Hitler called nerve gas his Siegwaffe, his secret victory weapon. In 1943, the British intercepted and decrypted German high command signals regarding tabun and sarin gas, codenamed “N-Stoff.” The Allies had nothing comparable! Sarin is a deadly “fluorinated” phosphonate developed by German chemists in 1939. The War Department was keenly aware that Hitler could utilize gas to drench London or the ports of embarkation in which our Allied troops would assemble for the Normandy invasion. Tabun is so deadly that a drop on the skin killed a victim in minutes by attacking the nervous system. The Luftwaffe had almost half a million weaponized bombs containing poison gas in its arsenal.

Navy Beach Battalion sailors training for D-Day and Dr. Davey’s invasion equipment. Note the gas masks in both photos.

Dr. Davey ran gas warfare seminars in the UK in preparation for the invasion of France. He ends a 23 March 1944 V-MAIL to my mother writing, “I have to go and give a lecture now on Medical aspects of Gas warfare and treatments. The Germans would be foolish to use gas, what with our air superiority and fine personal protective measures, but we must be prepared for it. Now, the greatest preparation consists in eliminating the fear in the men’s minds of gas; for there is nothing to fear.”

As a precaution, the War Department had weaponized botulinum toxins, designated “Agent X,” prepared for the cross-Channel attack. Gas protection equipment and self-inoculating syringes containing the botulinus antidote were distributed among the invasion troops. Blood samples were collected from enemy prisoners to determine if German immunization had been administered in preparation for biological warfare.

Less worrisome than germs or chemical agents, leading up to D-Day, was the German use of “radioactive dusting,” but as a safety measure, a handful of medical officers were trained in the use of Geiger counters. In addition, intelligence forces were poised to follow the Allied troops through Normandy in order to collect Nazi atomic bomb data and keep German scientists out of the hands of the Soviets.

After training in Salcombe on the English Channel Coast and with the Army in Swansea, South Wales, the 6th Naval Beach Battalion was attached to the 5th Engineer Special Brigade 12 April 1944 in order to achieve a closer coordination between the Navy afloat and the Army ashore during the invasion landings. In support of the 16th Regimental Combat Team, 1st Infantry Division, Commander Carusi's amphibious unit had the mission of providing battlefield medicine, establishing shore-to-ship communications, marking sea lanes, making emergency boat repairs, assisting in the removal of underwater obstructions, directing the landings and evacuating the casualties in the eastern Omaha Beach sectors code-named Easy Red, Fox Green and Fox Red.

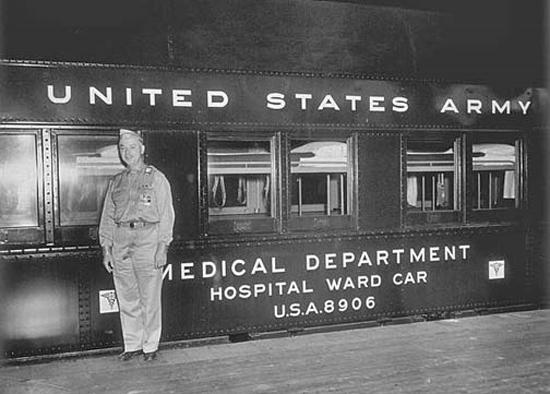

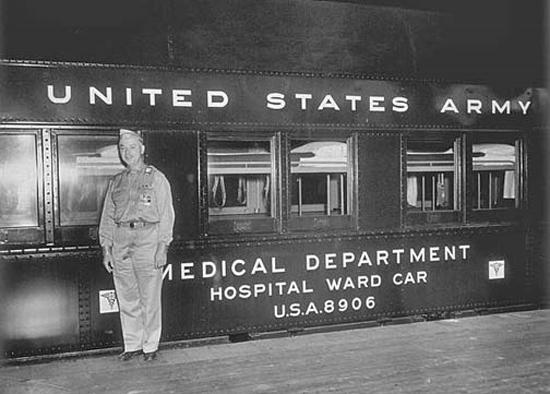

"Handle With Care" pastel by Julian Levi. A wounded serviceman on the Stokes litter is placed in the ambulance for a trip to the Norfolk Naval Hospital, Portsmouth, Virginia. (Gift of Abbott Laboratories) Picture of a Hospital Ward Car, part of a hospital train, on standby for debarking patients, at Hampton Roads, Virginia, 29 May 1943.

As tensions of the anticipated invasion were building in the United States, the Pentagon assured the nation that no efforts would be spared in caring for the casualties. In the May 22nd issue of LIFE magazine, in a photo spread titled American Invaders Mass in England, casualty predictions were signaling to the American people that D-Day was near. Battle wounded on the far shore would initially be evacuated back to England and later returned by hospital ships to U.S. ports in New York, Boston, Charleston, SC and Hampton Roads, VA. Hospital trains in the States would be carrying two hundred patients each, accompanied by doctors and nurses. American crews were being trained to lift litters through sleeper-car windows with a minimum of jostling. For security reasons, the public was unaware that Navy doctors and hospital corpsmen were scheduled to be on the invasion beaches to care for the initial wounded and the USN Beachmasters would then arrange for seaward evacuation. Prepared to receive heavy casualties on 90 LSTs waiting off the Normandy coast would be 355 Army and Navy trauma surgeons assisted by 2,520 hospital corpsmen and medics.

The 6th Naval Beach Battalion spent several weeks in the marshaling area near the town of Dorchester. Southern England was now becoming one vast military camp, crowded with soldiers and sailors, surrounded by barbed-wire entanglements and 2,000 Counter Intelligence troops. Assault personnel were prevented from leaving camp with secret information of the impending attack. During the period of confinement, no passes were issued and mail was forbidden. From May 26th through June 2nd, beach battalion personnel were taken into camouflaged circus-size tents and shown maps, photo-strips and sand table models of the assault beaches. The fifty-foot-long tables included plaster of Paris models and aerial photographs of the beach indicating the exact location of machine gun emplacements, pillboxes and beach obstacles. The battalion was assured that as a result of a massive air and naval bombardment of the Normandy coast, “every grain of sand will be turned over twice before the first wave hits the beach.” Intelligence officers emphasized that the Germans who manned the area behind Omaha Beach were second rate, older troops and there would be little resistance. “Don’t be afraid or ashamed of being afraid - just do your job!”

“June 3rd dawned hazy and windy along the south Devonshire coast,” recalled Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class Frank Snyder of B Company. “By 7:30 A.M., we of the 6th Beach Battalion and members of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade and 16th Regimental Combat Team of the 1st Infantry Division, with whom we had been sequestered in the Dorchester staging area for a couple of weeks, began loading up in six-wheel trucks. Entering into an endless convoy, we were transported down a highway to the port city of Weymouth. Along the way, noted among the few scattered houses, were small numbers of people who seemed to be only remotely interested in what was just another troop convoy.”

Invasion personnel are aboard British made LCAs in the foreground and 6th Beach Battalion platoons aboard LCI(L) 85, 88, and 89 at Weymouth, a seaside town in Dorset, England on the Channel coast. The New Yorker correspondent A.J. Liebling was aboard the USCG-manned LCI(L) 88, a 155 foot long / 300 ton Landing Craft Infantry (L)arge. This was the initial LCI(L) of the 5,000-ship invasion armada scheduled to make a landing on Omaha Beach. (1944 Cross-Channel Trip)

“By the time we approached the city of Weymouth,” said Snyder, “the attitude of the citizen population had drastically changed. The air was electrically charged. Crowds had collected at nearly every intersection. Flags - American, British and even a few French tricolors were seen in windows. Some children along the curbs were waving small hand-held flags. As Weymouth harbor itself came into view, the cause of all the excitement became obvious. Arrayed before our eyes was the most colossal fleet than even that historic seaport had ever witnessed. Ships, boats and barges of every type and description filled the harbor as far as the eye could see. The Weymouth townspeople, enduring five years of war, had seen many embarkations of ships and men, but obviously never of the size and scope of the panorama they viewed on this day.“

On 6 June 1944, sixty-five miles up the Hudson River from New York City, it was graduation day at the United States Military Academy, a day when 474 second lieutenants would begin their Army careers. Before marching off for breakfast, 22-year-old John S.D. Eisenhower was told by cadet commander Alan Weston, “Johnny, this is the biggest day of our lives-we’re graduating and at the same time D-Day has occurred in France.” IKE’s son was stunned. Weston recalled, “We weren’t supposed to let anybody else know because it was going to be announced to the corps as a whole three hours later.” At commencement, General Brehon B. Somervell, in his opening remarks announced, “I want to officially inform you that this morning United States and British forces landed on the coast of France.” Weston said, “All hell broke loose. Everybody went just wild.”

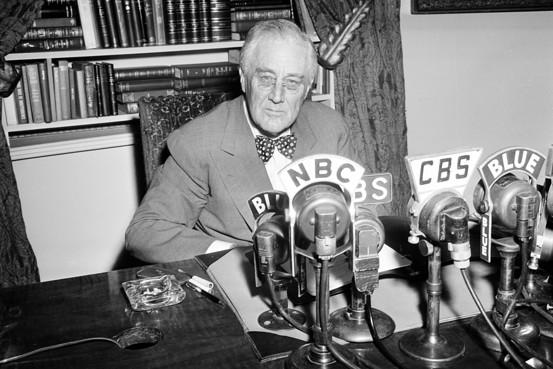

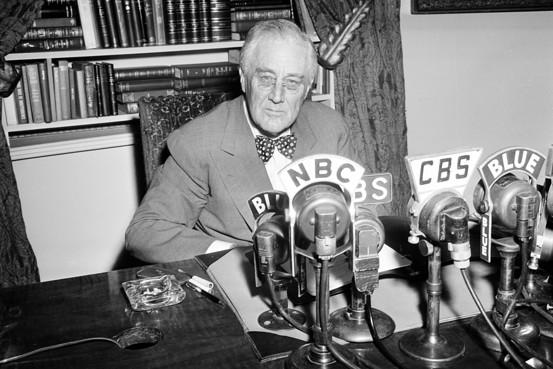

In the AP photo, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his moving D-Day prayer …”Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity…”

Early in the morning on D-Day, the usual crowd of several hundred gathered outside St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue for the first regular Mass. In New York’s Times Square, many Americans first learned from electronic bulletins that D-Day had begun. Over CBS radio, General Eisenhower announced, “The tide has turned…We will accept nothing less than full victory.” Although it had not been rung for over 100 years, the fragile Liberty Bell in Philadelphia began ringing, broadcast throughout the nation over NBC radio. President Roosevelt wrote a D-Day prayer he would deliver on the radio. By nightfall, 75,000 grateful New Yorkers had worshiped at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The Statue of Liberty, darkened since the war’s early days, was ablaze again – a full 96,000 watts.

Many years after D-Day, John S.D. Eisenhower wrote, “I have felt a secret discomfort that West Point’s Class of 1944 was savoring its graduation at the same time that boys younger than us were clinging desperately to the cliffs of Normandy or sinking in the English Channel, and yet finally pulling themselves together to launch the beginning of the liberation of Europe. It is a humbling thought.”

The Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, Dwight D. Eisenhower, arranged for fifty war correspondents to accompany the invasion troops and witness D-Day. Dispersed among 150,000 assault troops, headed for the Normandy beaches, journalists were promised “a front row seat” for what some predicted would be the most significant day of modern times. IKE considered war correspondents A.J. Liebling, Walter Cronkite, Don Whitehead, Andy Rooney, Lee Miller, Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn, Ernie Pyle, LIFE magazine photographer Robert Capa and many other reporters aboard landing craft an integral part of the invasion force.

During the evening of 5 June 1944, with landing craft LCI(L) 88 destined for the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach, war correspondent A.J. Liebling of The New Yorker, covered the Channel crossing of Headquarters and C-8 platoon of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion. Liebling’s D-Day classic “Cross-Channel Trip,” a masterfully detailed Normandy invasion account, was initially published in a series of the 1, 8, and 15 July 1944 issues of The New Yorker magazine, and later, The New Yorker Book of War Pieces, Mollie and Other War Pieces and Reporting World War II (Part II).

Aboard the LCI(L) 88, A.J. Liebling befriended the LCI Coast Guardsmen and on 5 June, during the 100-mile-Channel-crossing, played poker with Navy Beachmaster Joe Vaghi, “little Dr. Davey,” Army Lt. Miller, Ensign Reich and Commander Carusi. “That evening, in the wardroom, we had a long session of a wild, distant derivative of poker called ‘high low rollem.’ Some young officers who had come aboard with the troops introduced it,” wrote Liebling. “We used what they called ‘funny money’ for chips – five-franc notes printed in America and issued to the troops for use after they got ashore.” It was during the card game that Gene Carusi, an Annapolis “three-striper” and Washington, DC attorney informed Liebling his battalion would go ashore to organize boat traffic and provide casualty evacuation on a stretch of beach just behind the first wave of infantry. “In the game were three beach battalion officers, a medical lieutenant (j.g.) named Davey, from Philadelphia, and two ensigns - a big, ham-handed college football player from Danbury, Connecticut, named Vaghi, and a blocky, placid youngster from Chicago named Reich. The commander of the engineer detachment, the only Army officer aboard, was a first lieutenant named Miller.”,

Commander Carusi’s executive officers, aboard another LCI, were Lieutenants Ed Reardon and Henry Watts, both New Yorkers. In the event LCI(L) 88 took a direct hit, the 6th Naval Beach Battalion would avoid a complete decapitation at the top. In the event Carusi was wounded or killed on the beach, Watts would take over battalion duties, between the low tide mark and the high tide mark, in charge of the eastern half of Omaha Beach. As fate would have it, Carusi, was seriously wounded when he received a .30-caliber anti-aircraft shell through the top of one lung on the evening of D+2. After the war, Commander Watts became chairman of the Board of Governors of the New York Stock Exchange.

A.J. Liebling described Gene Carusi’s men as “sailors dressed like soldiers, except that they wore black jerseys under their field jackets; among them were a medical unit and a hydrographic unit. The engineers included an M.P. detachment, a chemical-warfare unit, and some demolition men. A beach battalion is a part of the Navy that goes ashore; amphibious engineers are part of the Army that seldom has its feet dry.” The LCIs were portrayed as “carrying specially packaged Army-Navy units for early delivery on the continent doorstep. Together they form a link between the land and sea forces.”

Early in the morning on D-Day, three U.S. Coast Guardsmen were hit by the exploding 88-mm shells as their LCI(L) 88 discharged her Army and Navy passengers at the exact scheduled time and beach location. Liebling was literally drenched in USCG blood, unable to see through his glasses. Coast Guardsmen Warren Moran, Rocky Simone and Bill Frere died valiantly getting the U.S. Navy’s initial medical detachment ashore Omaha Beach.

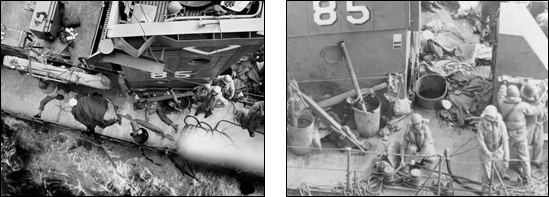

USCG film of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion going ashore “Easy Red” Omaha Beach at “H+65 MIN.” or 7:35 A.M. on D-Day. Beachmaster Vaghi, Comdr. Carusi, Ensign Reich, Cox Ed Marriott, Amin Isbir (KIA) and Lewis “little boats” Strickland are approaching the beach. Not far behind are John Hanley, Eddie Gorski, Frank Hurley, Bob Walley, Harold Roderick, Ray Castor, John Shrode, Andy Chmiel, John Dietzman, George Abood, David Catallo, Bob Millican, Norman Paul, Emil Candelaria, Al Silva, Howard Hampton, “little Dr. Davey” and the remainder of C-8 platoon. Note the corpsman holding a stretcher on the LCI(L) 88 port ramp. Army amphibians are lining up to go down the starboard ramp.

When Beachmaster Vaghi led his C-8 platoon ashore “Easy Red” Omaha Beach at 7:35 A.M. on D-Day, bodies of the dead and the dying littered the sand as far as the eye could see. The Army-Navy demolition teams, ashore since 6:33 A.M., were so badly decimated that only a few lanes were blown through beach obstacles and mines. With many casualties medically beyond help, Dr. Davey ordered his corpsmen to treat only injured personnel who could be saved. Soldiers and sailors were drowning in the surf and the initial phase of the invasion appeared to be a military disaster.

Maj. Charles E. Tegtmeyer, MC, regimental surgeon of the 16th Infantry, who landed on Omaha Beach at 8:15 A.M., described the disastrous conditions on Easy Red. “Face downward, as far as eyes could see in either direction were the huddled bodies of men; living, wounded and dead, as tightly packed together as a layer of cigars in a box.” Dr. Tegtmeyer noted that wounded men, lying on the exposed sand, were frequently hit a second or a third time. “At the water’s edge floating face downward with the arched backs were innumerable human forms eddying to and from with each incoming wave, the water about them a muddy pink in color. Floating equipment of all types like flotsam and jetsam rolled in the surf mingled with the bodies.”

In the cold Channel surf off the Fox Red sector of Omaha Beach, 6th Beach Battalion corpsmen James S. Brewer and Thurman W. Poe disembarked from an LCT (Landing Craft Tank) into deep water under heavy mortar fire. They were accompanied by a struggling Army captain. When the captain's life belt failed and he was in grave danger of drowning, Poe and Brewer went to the officer's rescue and brought him to the beach. Both corpsmen were awarded the Marine Corps Medal.

Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class Frank Snyder aboard an LCT approached the Easy Red sector on D-Day. “LCT 600’s hull grounded and, as the ramp dropped, we were greeted by a large explosion close aboard the bow of the craft. A few dead and injured were immediately seen on and near the ramp. I witnessed a soldier standing on the ramp who, at first glance, appeared to be waving a short white stick or baton,” said Snyder. “On closer observation, the object was discovered to be the man’s own ulna stripped of flesh, the bone gleaming white. An army medic and I reached the man at the same moment. Standing, stunned, as he was, the man, a major’s oak leaf insignia clearly seen on his collar, appeared not to comprehend what had happened to him. An artery in his upper arm was furiously pumping away his life’s blood. A tourniquet quickly staunched the flow, but we had to wrestle the man off the ramp and onto the tank deck…”

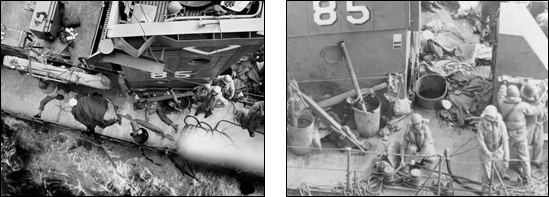

Tragically, not all the officers and enlisted men of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion made it ashore Omaha Beach on D-Day. At 8:30 A.M., "We could hear the screams of men through the voice tube" reported Coit T. Hendley, Jr., USCGR, commanding officer of LCI(L) 85. The '88's were hitting the ship. "The shells tore into the troop compartments. They exploded on the exposed deck. They smashed through massed men trying to get down the ramp. Machine guns opened up." The landing craft had been hit about 25 times, killing Beachmaster Jack Hagerty, Beachmaster G. E. Wade, Beachmaster Len Lewis, Senior Petty Officer George L. Abbott, Senior Hospital Corpsman John T. O'Donnell, from Hamburg, NY, Boatswain's Mate Alton E. Hudson, Radioman Thomas Irvin Simmons, from Flushing, NY, and Army combat engineers.

SIXTH Naval Beach Battalion supreme sacrifice on D-Day. The above photos were taken from the USS Samuel Chase looking down at the carnage on the USCG LCI(L) 85. Navy censors obscured details in the photos and removed the sinking of LCI(L) 85 from A.J. Liebling’s original Cross-Channel Trip manuscript .

Dr. John F. Kincaid, platoon C-9, said that moments before the fatal blast, Jack Hagerty “was assisting me in treating one of the casualties. He turned to lead his men ashore and I moved forward to treat another casualty. At that moment, a heavy shell landed aboard, killing Jack instantly. Wade, another of our officers, who was standing beside Jack at the time got it with the same shell.”

"Unloading of the Coast Guard-manned LCI 85 had to be stopped because the living could not climb over the dead" wrote Coit Hendley. The beach battalion doctors went to work, doing what they could for the wounded. "The deck was so slick with blood and cluttered with bits of flesh and dead and mutilated men that it was difficult to move from one part of the ship to another. There is no need to describe all the pitiful cases." No one will ever forget! "We had 15 dead and 30 wounded. Only four of the ship's crew were wounded. The other casualties were all from the beach battalion."

LCI(L) 85 made it out to the transport area, 10 miles from the beach, taking water slowly. After transferring the wounded to the USS Samuel Chase, Dr. Kincaid and Navy medical corpsmen who stayed to help with the casualties, climbed into a small boat. Commander Hendley reported that "they took their equipment and said nothing. They knew they were needed on the beach. How many of them are living now I do not know." LCI(L) 85 went to the bottom of the Channel. (Navy Medicine November 2000)

Correspondent Don Whitehead, who struggled ashore Easy Red at 8:39 A.M. with General Willard G. Wyman of the 1st U.S. Infantry Division, gave a depressing account. “There was no cover for the men on the beach. The Germans were looking down on them - and it was a shooting gallery.” General Wyman ordered Beachmaster Vaghi’s C-8 signalman Frank Hurley, of Brentwood, NY, to send urgent messages to the destroyers out in the Channel.

"I recall that we were about 200 yards west of a small draw on Easy Red marked on the maps as E-1 or Exit 1," said Whitehead. "A blockhouse had been built into the bluff above the dirt road that led inland. The German gunners manning an 88mm weapon had a clear field of fire to the west. They were firing at almost point-blank range at the landing craft and the troops trapped at the edge of the water."

"A radio call for help went from an army-navy beach team to a destroyer. We saw the destroyer come racing towards the beach and swing broadside, exposing itself to the fire of the batteries on the bluff. One shell from the destroyer tore a chunk of concrete from the side of the blockhouse. Another nicked the top. A third ripped off a corner. And then the fourth shell smashed into the gunport to silence the weapon. Always, in my mind," emphasized Whitehead, "the knocking out of this gun was a major turning point of the battle in our sector."

Army personnel of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade make a rescue and beach battalion aidmen provide plasma on the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach.

SIXTH Beach Battalion medical teams, forced to drag casualties from the surf toward the enemy's murderous guns, became casualties themselves. Casualties piled up on the beach with massive injuries: eviscerations, traumatic amputations, sucking wounds of the chest and massive head wounds. Richard Grewelle had to remove a soldier’s leg. “It was hanging by a string; I don’t know if he made it.” Under punishing fire, corpsmen worked up and down the beach and in the minefields, bandaging, splinting, giving morphine, and plasma. Navy doctors, often themselves injured, worked as they could to provide triage and give emergency treatment.

On Fox Red, Lt.(jg) Frank Ramsey, platoon A-1, was seriously wounded when flying fragments of metal tore into his back after a nearby burning half-track exploded. Dr. Ramsey, now 96, “felt like he was kicked by a mule in the back." The soldier being treated by Ramsey was killed outright. “Pharmacist's Mate Third Class Byron Dary, without regard to his own safety, went immediately to the aid of his officer, administered first aid on the spot, dragged the officer to a nearby hole for safety, and arranged for the officer's evacuation.” Refusing evacuation while on morphine, Dr. Ramsey provided triage instructions to his USN corpsmen.

At mid-morning, Easy Red was still under constant fire from small arms, mortar, and artillery. Guns from destroyers, cruisers, and battleships were battering heavily fortified beach emplacements and pillboxes which blocked important beach exits. Moments after a huge explosion from a German railway gun hurled a jeep into the air killing Coxswain Amin Isbir, Beachmaster Vaghi, with coveralls ablaze, and Dr. Davey, bleeding from the ears, both regained consciousness. Averting more death, Joe Vaghi and C-8 corpsman Bob Millican dragged away casualties and hauled off cases of hand grenades and two five gallon cans of gasoline from a nearby burning jeep. One of the many casualties saved was 6th Beach Battalion radio operator Torre Tobiassen, now 87.

After tending to soldiers and sailors on Easy Red, Corpsman Frank Walden, now 86, was himself wounded. Walden said he and 16-year-old fellow corpsman, Virgil Mounts, saw a shell explode near two Army personnel who were carrying a stretcher. When Walden and his friend went to treat them, another shell blew up, killing Mounts. Some of the shrapnel that went through Vigil Mounts remains in Frank Walden today.

6th Naval Beach Battalion Casualties

Killed in action: 4 Officers, 18 Enlisted Men

Wounded in action: 12 Officers, 55 Enlisted Men

|

|

|

Charles L. Abel, KIA |

Bronze Star Medal |

Morris W. Rickenbach, KIA |

On the Fox Green sector of Omaha Beach, ”All types of landing crafts were beached and many dead were on them,” said Corpsman Vince Kordack, now 87. “From time to time, bodies washed ashore in the surf. Some of these men would not be moved for some days to come. One of the fellows said my friend, Morris Rickenbach, was hit. The doctor went over to look at him and said, ‘Put a dressing on and leave him there.’ The way he expressed it meant he would die. Later, I looked over and he was turning white.”

The casualty rate of 6th Naval Beach Battalion medical personnel on Normandy D-Day was 27 percent. Five corpsmen did not survive:

PhM 3c Charles L. Abel (KIA)

HA 1c Virgil Mounts (KIA)

PhM 1c John T. O'Donnell (KIA)

PhM 2c John F. Peterssen (KIA)

PhM 3c Morris W. Rickenbach (KIA)

Less than a year after surviving "bloody Omaha," Dr. John F. Kincaid was killed during a kamikaze attack off Okinawa. Pharmacist's Mate Third Class Bryon Alfred Dary, who won a Silver Star on Omaha Beach, was killed on Iwo Jima in the Volcano Islands, February 1945, and posthumously awarded the Navy Cross.

Retreat was not an option on 6 June 1944. General Omar Bradley considered abandoning U.S. troops on “bloody” Omaha and redirecting the entire American assault through Utah Beach. Against all odds, the SIXTH Naval Beach Battalion managed to organize the invasion landings and provide casualty evacuation on the eastern Omaha Beach sectors code-named Easy Red, Fox Green, and Fox Red.

Excerpts from the Secretary of the Navy's 1943-44 annual report to President Franklin D. Roosevelt concluded that for 99 of 100 men wounded during the Normandy landings, the road to recovery began on the beachhead. Expertly trained and equipped Army and Navy medical personnel gave first-aid treatment of life-saving proportions to the initial assault troops during the amphibious attack. Medical care was exacting because of the nature and the severity of the wounds. By the use of plasma, control of hemorrhage and proper splinting, personnel of the Navy Beach Battalions were able to evacuate those injured whose lives might otherwise have been lost. Urgent life-saving surgery was practiced aboard LSTs and the majority of the 41,035 wounded reaching England for hospitalization were in excellent condition. Penicillin was a new but crucial component of the medical arsenal in the ETO. The mortality rate of the wounded evacuated from the invasion beaches of France was 3/10 of 1 percent.

"Omaha Beach,” Omar Bradley wrote many years later, “was a nightmare. Even now it brings pain to recall what happened there on June 6, 1944. I have returned many times to honor the valiant men who died on that beach. They should never be forgotten. Nor should those who lived to carry the day by the slimmest of margins. Every man who set foot on Omaha Beach that day was a hero."

General Bradley's First U.S. Army Report of Operations concluded, "Combined training with the Navy Medical Department is a must. Too much cannot be said about the part which the navy played in the early days of the landing operation."

The Combat Medical Badge (Army Regulation 600-8-22) was conceived 1 March 1945 by the War Department. The badge was intended only for medical personnel who served under direct fire with the infantry. The CMB is awarded to any member of the Army Medical Department, at the rank of Colonel or below, who are assigned or attached to a medical unit which provides medical support to a ground force engaged in active combat. Retroactive to 6 December 1941, the CMB could also be awarded to U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force medical personnel as long as they met all the requirements of Army medical personnel.

Veterans of World War II who were awarded the Combat Infantry Badge or Combat Medical Badge are entitled to receive the Bronze Star Medal. The awarding of the Army Bronze Star was authorized in 1947 to honor the accomplishments of infantrymen and medics who endured great hardship.

|

August 30, 1944

Dear Lieutenant Hall,

I am Morris Rickenbach's brother-in-law, and since his mother is as yet unable to concentrate on writing a letter, I am taking this opportunity to answer your letter for her.

It is impossible to find words to show our appreciation for your most enlightening and beautiful letter. There is little anyone can do to heal the wound that Rick's passing has inflicted on his mother and father and the rest of us who knew and loved him, but the message of condolence that you and others, who served in the same company with him, have sent or delivered in person to us have been like a soothing salve that has helped us more than any of you will ever know to bear the sorrow which his passing has brought to us.

If you are ever in this vicinity and have the opportunity to pay us a visit, please do not hesitate to do so. It may be of interest to you to know that so far we have had the pleasure of seeing Lieutenant Collier, Dick Grewelle, Dennis O'Leary, Russell Dickinson, and Joe Wojnowski. The latter hitch-hiked all the way from Elizabeth, N.J., to bring Rick's mother his identfication tags and a religious medal he had been wearing.

All these gestures of friendship and kindness, we can never hope to repay. All we can do is thank you- - - thank you all from the bottom of our hearts, and pray that God will watch over and protect all of you.

Sincerely Yours,

Robert Maycott

P.S. Your letter to Rick's mother and father was addressed to Camden, New York, instead of Camden, New Jersey.

|

Marking the 68th anniversary of D-Day, 6 June 2012, Commander Erik R. Nilsson, USN, Beachmaster Unit One in Coronado, California announced that medical personnel of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion would receive the Combat Medical Badge and Bronze Star Medal for actions during World War II, specifically during Operation OVERLORD, the Allied invasion of Normandy, France. Veteran corpsman Frank Walden of Walnut Creek, CA traveled by plane with his family to Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, outside San Diego, for the BMU One change of command ceremony. Beachmaster Unit ONE officers and personnel are direct descendents of the World War II beach battalions. Mr. Walden was awarded the CMB and Bronze Star in a very moving ceremony.

Beachmaster Unit One planned to conduct an East Coast presentation ceremony aboard the INTREPID Sea, Air & Space Museum on the West side of Manhattan, Pier 86, near where the 6th Beach Battalion sailed from New York 68 years ago. Due to hurricane Sandy, the Veterans Day ceremony is now scheduled on 11 November 2012 at 11:00 A.M. aboard the Battleship NEW JERSEY in Camden, NJ. The NEW JERSEY is a particularly fitting venue given that corpsmen Charles L. Abel (KIA) was from Lancaster, PA and Morris W. Rickenbach (KIA) was from Camden, NJ.

By order of the Secretary of the Army, 15 March 2012, Permanent Order 075-15 through 075-22, the following sailors of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion are to receive the Combat Medical Badge and Army Bronze Star Medal, for actions during World War II.

MEDICAL OFFICERS

COLLIER, James F., Lt(jg), B-6

DAUGHTREY, John E., Lt(jg), A-2

DAVEY, J. Russell, Lt(jg), C-8

ETZL, Michael M., Lt(jg), C-7

GUYTON, Eugene D., Lt(jg), B-5

HALL, Ralph A., Lt(jg), B-4

KINCAID, John F., Lt(jg), C-9 (KIA)

PARKER, Joseph L., Lt(jg), A-3

RAMSEY, Frank M., Jr.,Lt(jg), A-1

ROSTER OF ENLISTED MEN

ABEL, Larrabee, PhM2c, C-7 (KIA)

ABOOD, George Jr., PhM3c, C-8

ABRAMS, Robert G., PhM3c

AIESI, Paul S., PhM1c, B-6

BANHAM, Edwin P., PhM3c, A-3

BARNES, Donald C., HA1c, B-5

BIRMINGHAM, Sammie Jr., PhM3c

BISH, Emerson Jr., PhM3c

BLACK, James F., PhM2c, C-9

BORDEN, Richard W., HA2c, B-5

BRENNAN, Joseph R., HA1c, B-5

BREWER, James S., PhM3c, A-3

BUCKLES, Kenneth W., HA1c, A-3

BURROUGHS, Don A., PhM2c, C-7

CALLAGHAN, James P., HA1c

CAMP, Frederick, HA1c, B-4

CANDELARIA, Emil J., HA2c, C-8

CATALLO, David A., HA1c, C-8

CHMIEL, Andrew R., PhM3c, C-8

COOK Eugene R., HA2c, B-6

DARY, Byron A., PhM3c, A-1 (KIA)

DEVLIN, Joseph A., PhM3c, A-3

DICKENSON, Russell W., HA1c, B-4

DIETZMAN, John G., PhM3c, C-8

DOMINICO, Donald M., HA1c, B-6

DUNCAN, Hiram, PhM2c

ECKER, Jess C. Jr., HA1c

FUDA, Dominic P., PhM3c, A-3

GIFFORD, Gilbert C., PM3c

GINSBERG, Jerome, HA1c, B-6

GLASH, Norbert L, PhM2c, B-4

GOULD, Jay, PhM1c

GREEN, Carl J., HA1c

GREEN, John R. PhM3c

GREWELLE, Richard E., PhM3c

HAMPTON, Howard W., Jr., PhM3c, C-8

HANSON, Edward F., HA1c, C-9

HIGNEY, John T., PhM2c

HOUSER, Francis X., HA1c, C-9

JACOBS, Ronald W., PhM2c, C-9

JOHNSON, Arnald L., PhM3c, A-3

KISH, Jules B., PhM3c

KLEIN, Harold M., HA1c

KORDACK, Vincent A., PhM3c, B-6

LE MAR, Darwin D., PhM3c, B-5

LUKASNEWICZ, John M., PhM2c, A-3

MAY, David H., PhM3c, B-5

MCMEARTY, Edward F., Jr., HA1c, B-4

MERVIS, Louis J., PhM2c, C-9

MILLICAN, Robert, PhM3c, C-8

MOORE, Harry W., PhM3c

MORTIMER, James T., PhM1c

MOUNTS, Virgil, HA1c, C-7 (KIA)

MULLOY, George T., Jr., PhM3c

NEWMAN, Edward W., PhM1c, C-7

O’DONNELL, John T., PhM1c, B-5 (KIA)

PAUL, Normand, PhM2c, C-8

PETERSSEN, John, PhM2C, C-9 (KIA)

POE, Thurman W., HA2c

RADZISZEWSKI, Ben A., HA1c, B-4

REMPFER, Earl W., PhM3c, B-5

RICKENBACH, Morris W., PhM3c, B-4 (KIA)

ROBIDOUX, Francis A., HA1c, C-7

SCOTT, George H., HA1c

SILVA, Alvaro, HA1c, C-8

SNYDER, Frank D., Jr., PhM3c, B-5

TOOMEY, Daniel C., PhM2c, A-3

VOSS, Stephen H., HA1c, C-9

WALDEN, Francis M., HA1c, C-7

WHALEN, George W., HA1c, C-7

WILLIAMS, Earl F., PhM2c

WILSON, Myron D., PhM3c, C-9

WINANS, Murel, HA2c, A-1

WOJNOWSKI, Joseph H., PhM1c, B-4

ZWERLING, Norman, PhM3c

|

August 15, 2001

Dear Mr. Davey,

My dad never talked about the war as I was growing up until after my Mom passed in 1973. Maybe a tragic and early death brings back these terrible memories in one's life. The story was almost always the same one about when he landed on the beach of Normandy.

I believe his ship landed on the 3rd wave and this is how the story went: the beach was deserted except for Dr. Hall, Rickenbach and Dad. They were walking very slowly in a straight line, Dr. Hall led, Dad was next and then Rickenbach. They were oblivious to their surroundings, maybe it was fatigue, maybe it was shock, when suddenly Dr. Hall realized that there was shelling going on all around them. He yelled to Dad "run Wojo." They started to run and Dad turned to yell to Rickenbach to hurry but when he turned around, Rickenbach was hit and his body exploded right then. Every time he told me this story, it was like I was hearing it for the first time because he would just stare straight ahead and included every detail as though he were reliving it. I could see in my head the whole thing playing out as though I was actually there. And that's all he would say about that incident. The story ended there.

In the early 1990s, Dad told me he had a strong desire to visit Rickenbach's grave site. I did some research and found out that he was buried in a Burlington County, NJ cemetery by the name of Beverly National Cemetery. It's about an hour and a half from our home. That started our yearly ritual. On June 6th of every year that was to follow, Dad and I would go and visit Morris Rickenbach, Jr., at section F, grave # 1560 at the Beverly Cemetery. Mr. Rickenbach's date of death was June 6, 1944. We continued that ritual until the year Dad couldn't walk anymore.

My dad enlisted in the Navy on January 10, 1942 until December 10, 1945. He was a Pharmacist's Mate First Class. I hope this helps you Ken. And if you ever get a chance, would you send that letter from Rickenbach to Dad.

Thank you,

Eleanor

|

|

|

|

Ed Banham |

Frank Snyder |

John Higney |

|

|

|

Mural Winans |

Joe Brennan |

Richard Borden |

|

|

|

Dr. Mike Etzl |

Vince Kordack |

Dr. Ralph Hall |

|

|

|

Andy Chmiel |

John Dietzman |

Dr. James Collier |

|

|

|

David Catallo |

Dr. Russ Davey |

Howard Hampton |

Army and Navy aidmen were universally praised by D-Day veterans as the bravest of the brave. In Dr. Lee Parker's A-1 platoon, 19-year-old Jerome Alberts described the D-Day conditions on the Fox Red sector of Omaha Beach. "Thousands of mangled bodies were strewn about, and hundreds of others were in agony awaiting evacuation. The task lay before us. Signal the Ships in! Stretcher bearers! Corpsmen! There was not an idle man. By noon, landing craft and Rhino ferries were taking them to hospital ships. I take my hat off to the medics, both Army and Navy. The work of Dr. Lee Parker, of our platoon, stands out in my mind. That man was everywhere and every place. One minute he was ten feet from me giving a man plasma, five minutes later he was aboard a beached LCT, treating scores of other wounded." (Navy Medicine November - December 2000)

The Herald Journal, Greensboro, Ga.

August 2, 2012

With his family gathered around him, Dr. Lee Parker was presented with the Bronze Star Medal and Combat Medical Award, in his hospital room at St. Mary’s Good Samaritan Hospital in Greensboro.

Rear Admiral (ret) Jay Miller conducting the prestigious ceremony beginning with reading the announcement of the two awards to be bestowed upon Joseph Lee Parker, Jr., M.D., LT (jg), better known to Green County community as, Dr. Parker.

Both honors were presented to the physician for his dedicated service as a young medical officer in the 6th Naval Beach Battalion on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

As family, friends, and hospital staff listened, Rear Admiral (ret) Miller read the following:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Bronze Star to Lieutenant Lee Parker, Medical Corps United States Navy, for service as set forth in the following:

For exceptionally meritorious medical service in the performance of medical duties on Omaha Beach during “Operation Overlord,” the Allied invasion of Europe on D-Day, 6 June 1944 and the days following. As a member of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion and senior Naval Medical Corps Officer on Fox Red Sector, Lieutenant Parker greatly enhanced the medical care rendered during the initial combat operations. His medical expertise and devotion to duty in the face of enemy fire were significant in saving lives and comforting wounded assault troops.

By his outstanding leadership, dedication to duty and medical skills, Lieutenant Parker reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

With a glimmer in his eye, Dr. Parker acknowledged the honors.

Back to Top

Back to Top